A short reflection on Soundgarden, Nietzsche and teaching that has been a long time coming.

A short reflection on Soundgarden, Nietzsche and teaching that has been a long time coming.

Last Fall, in November of 2014 sometime, in the Communication and Gender I was teaching, we were talking early in the class meeting about the impact of historical constraints on contemporary gender identity. I can’t even recall which article we’d read for that day; as sometimes happens–which I think is cool and which is part of the point of this reflection–we drifted far afield from the article. I could have played the role of “teacher reconnecting the discussion to the reading,” which I think I do pretty well when I try but which I find too boring to do most of them time.

Instead, as I much more often do, I tried to make a connection I hadn’t planned to make: I riffed for a while (a very long while, basically until class ended) on Nietzsche. Sometimes my random riffs precipitate unhelpful, poleaxed silence, and then I kick myself for being a lousy teacher, the worst kind of anti–Freirean “hey, look at all the things I know that you don’t, and sit there while I talk about them” clown. But on that day, I honestly saw and felt the vibe of most students, nearly all 30 of them, actually engaging as listeners, talking to each other, offering stories and comments and challenges while still riding on the waves of talking that I was spewing. Really. They were definitely digging Nietzsche’s ideas about historical constraints (especially moral ones) and how we might relate to them by living our own lives in the present. We talked about Nietzsche’s disregard for false moral outrage, moral outrage that has no root other than “wait, you’re not supposed to do that!” responses having nothing to do with being truly negatively affected by others–using traffic merges, speed limits and megastore checkout lines as examples. We talked about why he thinks that the worst part of cheapening our moral outrage through being pathetic little cops-for-the-received-moral-system is that it destroys moral growth by always forcing us to live through past principles, fears and limits. We talked about how the effects of an artificially constrained, backward-looking moral sensibility affect us not just socially but interpersonally and in our own living through our own bodies, too.

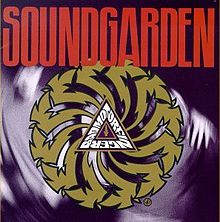

All worth linking up to gender, sure, but as I got in the car to drive home I was rehashing the class discussion in my head (like I often do), and I started to wonder where all the sudden passion for Nietzsche came from; why did I burst forth with all this abrupt Nietzschean verbosity, today of all days, years from reading or even talking about the guy? As I was turning this over in my head I flipped through my CD wallet and noticed the disc I’d driven to work with in the morning: Badmotorfinger. If a person’s jaw can actually drop and leave the mouth all agape, not just in cartoons but in real life, it must have happened then; maybe some kids glancing into my car noticed it and pointed and laughed, I don’t know. But I popped Badmotorfinger back in, listened again on the drive home and kept “Duh!-ing” myself repeatedly over the next hour as the music played. Why was I so dumb as to wonder what put Nietzsche in my head, and more importantly and thickheadedly, why had I just now realized, in November 2014, what Badmotorfinger is about, the entire album, song after song after song?

All of a sudden it seemed so obvious. Like a twit, I’d been most drawn to Superunknown first, because of all the catchy radio songs that I already knew. That album’s plenty good, sure, but the idea that it took me so long to appreciate how much more poetically nuanced, musically anchored in the lyrical themes, and incisively focused Badmotorfinger is, by comparison–wow, what a twit indeed.

To just briefly sketch the argument, starting as the album starts: “I’m gonna braaayyykk … I’m gonna break my … I’m gonna break my rusty cage and ruuuuuuunnnnn.” What a gorgeous encapsulation of the self under patriarchal Christianity, glossing how narrow ideas about human experience don’t just set us up against people who look different or who are too poor or who don’t pray to our deity–they even more directly set us up against ourselves, so that we hate ourselves and try to thrash against nails and chains and boiling tortures that we willingly use to cage ourselves. We have to, Chris C and Fred N both insist, break ourselves first in order to remake the world. Then once we’ve self-abnegated, we ramp up the loathing by channeling our energies into ludicrous competitions for the same worthless, narcissistic approbations we and everyone else have been “sold,” so that when we’ve “looked in the mirror things aren’t looking so good” because we’re “outshined” by, of all things, the light reflected in that mirror–not other people defeating us but by us defeating ourselves, by being “mystified,” by looking stupidly to others for evidence of our worth. That’s just the first two tracks on a hour-long journey where Nietzsche is reflected through early 90s American culture, the whole way through. Listen and I promise you’ll hear it too. Cornell’s justifiably celebrated voice does more than just kick aesthetic ass, “outshining” nearly every other voice in the hard rock vocal tradition here; it is genuinely performative, bloodying up each lyric with the warmth and passion of feeling.

Sometimes the public and the mainstream press gets it right, though; for me, the two most magnificent statements are the two most famous songs, “Jesus Christ Pose” and “Drawing Flies.” As for the first track, I swear I could teach a five-week, at a minimum, unit on Nietzsche where every day we played this song to open class then focused the next few hours of discussion on one particular verse. As for the latter track, the poetry (by which I mean both words and vocal performance) is brilliant, and quite precisely evocative of existential angst as much as any Sartre I’ve read: What a superb use of what is known in hideous patriarchal poetry terms as “feminine” cadence, the “weak,” refusal–to–stress–the–end–syllable cadence that goes way beyond physical exhaustion in this song to reflect abject personal surrender, a cadence not so much surfing on as drowning amid the tumult of uneven and unpredictable line breaks: “Sitting here like uninvited company … Wallowing in my own obscenity … I share a cigarette with negativity … Leaning on the pedestal that holds my self denial … Firing the pistol that shoots my holy pride … Sitting here like wet ashes with exes in my eyez and drawing fliiiiieeez.” And still, even amidst this monochromatic sketch of bloodless existential squalor, multiple meanings are in play, circling around the lyric as “drawing” can be heard not just as “beckoning” but, in conjunction with the emphatic cartoon of the crossed–out eyes of death, as an act of creation, as an act of making the very symbol that marks one’s refusal to make. Wow.

I think class this day was a success, regardless of what article we’d read. But I also know that Badmotorfinger reminds me of the dangers of the Jesus Christ Pose, the narration sickness that Freire and Nietzsche both accuse most professors of poisoning their classes with. What I hope I avoided is just giving students nothing other than that. What I hope I did, instead, was give them just enough of a taste of Nietzsche that someday in the future, when a student is getting into her car (to merge or to speed or just to pop in a CD), she might reflect on the source of her immediate moral outrage, on whether it’s useful to her or not, and what she might do with it to help remake our calcified world. Hell, Chris Cornell doesn’t have a PhD, but he planted his seeds mighty well, so I can dream.