You know that I adore the 33 1/3 series of books…the little ones, each exploring a single album. We’ve talked about these; you might even have a couple, I can’t recall. You might remember that I submitted a few years back, with DLH who watched that amazing Nick Cave show with us, a proposal to write one on Cave’s Murder Ballads, and the editors rejected it in favor of another proposal for the same album submitted in the same call. That book is due out soon, and to say that my expectations for it are arch–skeptically high would understate the case. But usually, these books are great—each one situates the chosen album in some quirky slice of the temporal, local, sociocultural loaf that it has helped to constitute for listener–lovers. I know you care about that as much as I do, about placing music in context—this is why I wish I wasn’t always in meetings during your Prog On show, and also why after creating the constraint that my blog entries from now forward will be addressed to a specific person, I chose you first.

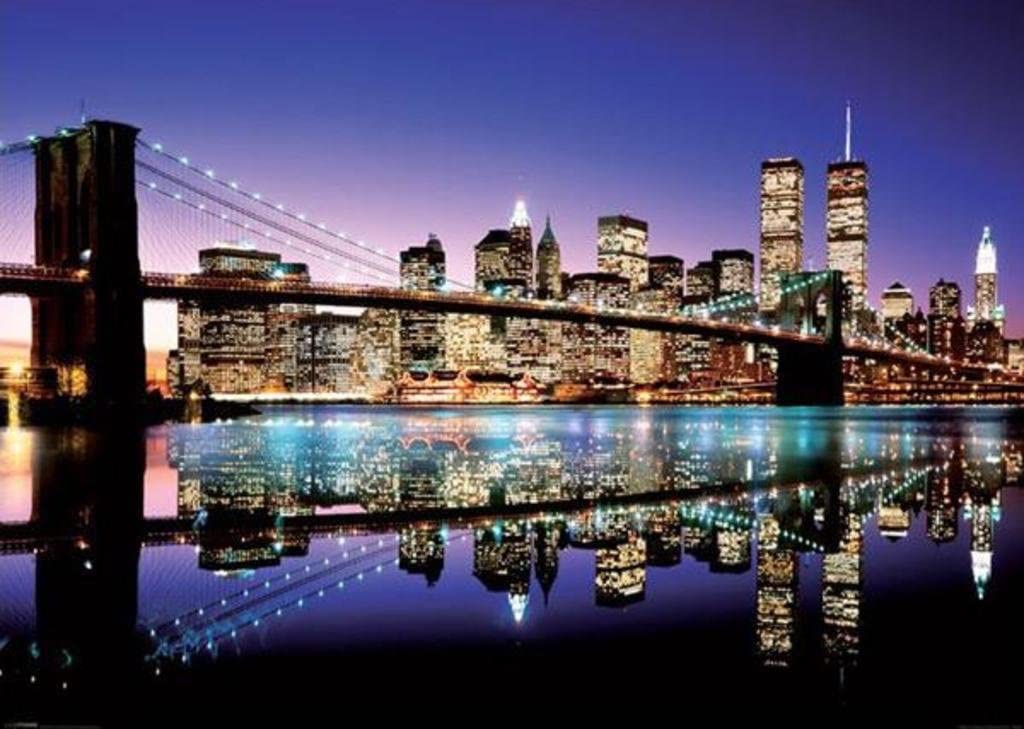

No matter how adept the author in any 33 1/3 effort, of course, as even these writers themselves would attest I suspect, none of these books can achieve nearly as well as an album itself can that special aesthetic singularity of making us live into a particular time and place through engaging the text. Sound has this in common with scent, the ability to immerse us in memory so deeply that we feel as if we are reliving it. With the exact right sound or scent, we can close our eyes years later and see it all again, sharply and in focus; we can feel the precise temperature of the air making the hairs on our skin bristle. I know that because of your high school life a short train ride away in suburban Connecticut you, like me, are well acquainted with the way that New York confronts the senses like no other place on earth, and that once we’ve spent time there we are changed forever in both body and mind. Nothing brings us back there like the sounds and scents. I wonder if this greater–than–other–senses quality that sound and scent have, to enliven remembered experience again, is down to these two senses depending on physical material traveling through air to reach our perception, depending on bringing vibrating stuff inside our ears or noses that then immediately passes away again even as we hear and smell. Do these two senses demand that we are always already remembering something that is on its way to departing from us even as we begin to sense it, in contrast to the light that keeps assaulting our eyes continually, to the sticky heaviness that depresses our fingertips so long as we touch, to the acrid pungencies that linger on our buds after we have swallowed or spat?

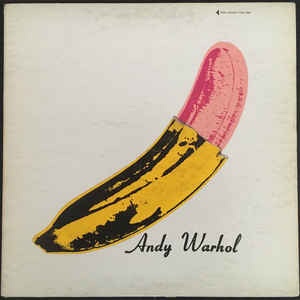

The Velvet Underground and Nico is without question partly about what we swallow and what we spit, in song after song. Every note, every syllable of this record pulsates with questions like, What do you find around you, when you are thrust into the City? What will you take in, among that which you find? What will you repudiate? And none of this is explored in any depth in what is the most disappointing 33 1/3 book I have read so far, the one about this album. Its author, a studio owner and producer inspired to get into the music business by VU, devoted all of his attention to ferreting out the tiny, disputed details about where and when and how the album came to be recorded and issued by its label. It’s an unusual and interesting story, to be sure, but I’m not certain I could name any historically important album I know in which the relationship of musical text to final commercial product is less consequential to the feeling of engaging the art than on The Velvet Underground and Nico. For this album, among all of them, the 33 1/3 author is completely missing the point—the sharp, biting point of fear and curiosity, the blade’s edge of vice and thirst for experience, the thrust of orgasm and self–denial that drips from its every reverberation in my ears. Studio time controversies and disagreements about which producer remembers what? Are you fucking kidding me?

Perhaps I hear this music the way I hear it because unlike this author, as you know I came to it belatedly and thereby found in it a history of existential aching and confusion and questioning that I never knew was in me all the while, in the same way that I came to New York as an adult, alone, for the first time in November 1988 as a first–year college student after several previous times of quick, safe–inside–the–car drives–through with my grandparents, on rare vacations as a Florida kid, to see them in New Jersey or to visit my Aunt Judy’s family in Long Island. As a kid, looking at the Manhattan’s skyline or Brooklyn’s shoreline through the window was like looking at Oz: New York City was great and terrible at once, a place where anything could happen and you’d better watch your ass because anything probably did happen. New York was the conceptual locus for me of all the knowledge that I would someday have as a genuine adult who might taste things and read things and even, maybe, is it really possible, have actual sex someday. New York was the living, teeming human transubstantiation of Eve’s fruit—no wonder they nicknamed it the Big Apple. And I’ll tell you, having at least a measure of terror suspended in the heady mead of my excitement about NYC was mighty useful when, on that first solo trip from school in Boston to Aunt Judy’s on Long Island for Thanksgiving break, I had to change buses in Port Authority and had a random guy come up to me on the bus deck and give me the hard sell that he worked for the MTA and wouldn’t I like help finding my next bus deck and help with my heavy bag and I should just follow him up this narrow stairwell and he’d show me and I went dutifully halfway up before my doubts finally gave me the gumption to say no thanks, I’ll find it by myself. Whew. It’s what I wanted more than anything else, from the City, to try for a change to find my own way.

Away from the big city…where a man cannot be free…of all the evils of this town…and of himself and those around

But that’s always a lie, of course. I have never found my own way. I found New York, as a white man who moved there because I chose it a little more than three years later, differently than many others find it. I have always had powerful guides even when I thought I was setting out on my own, starting that same Thanksgiving break with my cousin Joan who spent a day later in the trip exploring South Street Seaport with me. I’ve had guides I knew intimately and guides I will never meet except through technologies that pass sounds and writings on to me. Unlike you in that small auditorium in Boston, you lucky bastard, I’ll never meet Lou Reed, Rest In Peace, and it’s likely just as well because I’m quite confident that if we met he would complicate my deep respect for his vigorous energy and artistic searching and hyperarticulate literary sensibility and insatiable drive for experience and progressive concern for society’s most marginalized by also manifesting much less respectable qualities like blank dismissal and seething arrogance and incomprehensible violence and abject self–loathing. And in every single one of those dimensions on both lists, he is the ultimate one–person reflection of the City he loved and encapsulated, over and over again, in art.

As you and I both agree and many critics confirm, Lou Reed’s masterpiece is an album simply titled New York. I bought this album soon after its release, in early 1989, about ten weeks or so after my bus trips through the City and after my skulking, chastened, away from the fellow lurking in the Port Authority and after my day with Joan. When you and I listen to it now, in the context of a landmark election in November 2020, I know we both deeply feel its uncanny chill from the standpoint of political perspective: This album sounds, for all the world, like it was written not in the summer of 1988 but instead in the summer of 2020 in direct response to the Trump regime and to the COVID–19 pandemic and to a social media hellscape simmering with viral vid egoist numbskulls; it even namechecks both Trump and Giuliani, in the same verse of one song. Talk about prophetic. I can’t recall precisely why I bought it, as I had not yet heard even a note of Velvet Underground to that point in my life—I might have heard Dirty Blvd. or Busload of Faith on WBCN while you and I were at work, making those copies. I couldn’t have understood then how you would become my guide to Lou Reed and to so much other transformative music, or how Lou himself would became my guide to the New York that shocked and awed me just ten shorts weeks before.

As you and I both agree and many critics confirm, Lou Reed’s masterpiece is an album simply titled New York. I bought this album soon after its release, in early 1989, about ten weeks or so after my bus trips through the City and after my skulking, chastened, away from the fellow lurking in the Port Authority and after my day with Joan. When you and I listen to it now, in the context of a landmark election in November 2020, I know we both deeply feel its uncanny chill from the standpoint of political perspective: This album sounds, for all the world, like it was written not in the summer of 1988 but instead in the summer of 2020 in direct response to the Trump regime and to the COVID–19 pandemic and to a social media hellscape simmering with viral vid egoist numbskulls; it even namechecks both Trump and Giuliani, in the same verse of one song. Talk about prophetic. I can’t recall precisely why I bought it, as I had not yet heard even a note of Velvet Underground to that point in my life—I might have heard Dirty Blvd. or Busload of Faith on WBCN while you and I were at work, making those copies. I couldn’t have understood then how you would become my guide to Lou Reed and to so much other transformative music, or how Lou himself would became my guide to the New York that shocked and awed me just ten shorts weeks before.

Caught between the twisted stars the plotted lines the faulty map that brought Columbus to New York…Betwixt between the East and West

The album New York is extraordinary, and the money I recently spent on the multidisc reissue is worth every penny. Thanks for discussing it with me on the second episode of our show K and K’s Trakk Yakking, which will soon be hosted on this site (readers stay tuned!). I hope you take me up on your end of our Lou Reed Reissue Challenge and buy it for yourself; I promise you won’t regret it. I have certainly not regretted completing my end of the bargain by securing my other recent Reed–reveling reissue splurge, the box set that encompasses all of his solo albums between VU and New York. That luscious set is teaching me that the title New York applies equally well to all of his work, even the not–so–masterpieces, even the one titled Berlin, because in all of his work Lou brings me back to the City, every time, in every moment. In Reed’s music, all of it, people are weird and wonderful and do not care what Lou or you or I think about their weirdness or their wonders. But they care desperately what others think, and they bleed for these others and sweat for them and dance for them and put poison in their veins for them and drive cars and motorcycles for them and put on outrageous outfits for them and cum for them and die over and over for them and also live for them and holy moly do they all hate LA, every one of these people, and they hate every other place that is not New York. They live in bars and on stages. They try to write poems and novels. They sit slumped on the sidewalks where they sleep, begging us to make eye contact and begging us not to make eye contact, both at once. They steal from us in their disgusting European suits and dresses. They wish we wouldn’t stand so close. They just walk up and start talking to us, complete strangers, but if we try doing that we will be withered into dust by their look. These people know how to navigate because the Manhattan orthogonal grid of streets doesn’t just make conceptual sense, it grows like an antifreeze–in–the–gutter fungus right into our legs, my Florida legs and your Parisian–Connecticut legs, and we stop having to think about the City blocks as if they could ever have been organized in any other way. When we need a question answered, they will stream past us and render us completely invisible with their indifference, and when people with murder in their hearts and wallets come down the street every stranger will lock together with us in an iron phalanx of human solidarity to crush them. Every possible sin can be sinned here, always, all the time, and no one but us will ever take on the weight of our sins here. No one.

Writing here that I grew up in New York, despite spending my childhood in Florida and then my college years in Boston with you just before moving to Manhattan, would be not a misstatement but rather my second understatement of this piece. While living on 30th Street and 3rd Avenue in a rent–controlled apartment that shared an interior wall across apartment buildings in that strange in–NYC–many–buildings–have–just–two–independent–walls way with the former studio in which Miles Davis recorded Kind of Blue, and while working in a 24–hour copy store just off Union Square in the West Village (the scene of this photo, taken in 1989 shortly before I worked there and the year New York by Lou Reed was released), all of these things happened in my life for the very first time: I paid my own rent; I was unemployed for weeks and mooched off a friend to survive; I learned to organize and lead a group of coworkers; I went to drug–drenched raves in former churches and drank in seedy bars unlike any I’d ever find anywhere else and started smoking; I lived with a girlfriend, in a tiny apartment barely fit for one where we tried for several weeks to cram three of us; months after we broke up, I finally had really great sex, with a woman who spelled her name in the unusual manner of a famous musician you love and who was so confident and exciting that I almost chose to stay in New York for her even though she wanted no part of that and whose dark, sultry eyes and silky, curling lips I can still remember now as viscerally as if Lou Reed wrote about them; I cheated, with a woman I knew from college who was a cynical manipulator but who I chose to embrace anyway; I fell in unrequited love with a kind–hearted woman from Wisconsin who has the Best Hair in Human History and who took me to the New York Democratic Party Gala the night Bill Clinton was first elected; I let down a close friend who was devastated after a breakup by neglecting him because I was so overwhelmed with the pace and possibility of the City that was around me; I forged a bond of friendship that remains the strongest in my life, nearly three decades later. In New York, I grew up.

Writing here that I grew up in New York, despite spending my childhood in Florida and then my college years in Boston with you just before moving to Manhattan, would be not a misstatement but rather my second understatement of this piece. While living on 30th Street and 3rd Avenue in a rent–controlled apartment that shared an interior wall across apartment buildings in that strange in–NYC–many–buildings–have–just–two–independent–walls way with the former studio in which Miles Davis recorded Kind of Blue, and while working in a 24–hour copy store just off Union Square in the West Village (the scene of this photo, taken in 1989 shortly before I worked there and the year New York by Lou Reed was released), all of these things happened in my life for the very first time: I paid my own rent; I was unemployed for weeks and mooched off a friend to survive; I learned to organize and lead a group of coworkers; I went to drug–drenched raves in former churches and drank in seedy bars unlike any I’d ever find anywhere else and started smoking; I lived with a girlfriend, in a tiny apartment barely fit for one where we tried for several weeks to cram three of us; months after we broke up, I finally had really great sex, with a woman who spelled her name in the unusual manner of a famous musician you love and who was so confident and exciting that I almost chose to stay in New York for her even though she wanted no part of that and whose dark, sultry eyes and silky, curling lips I can still remember now as viscerally as if Lou Reed wrote about them; I cheated, with a woman I knew from college who was a cynical manipulator but who I chose to embrace anyway; I fell in unrequited love with a kind–hearted woman from Wisconsin who has the Best Hair in Human History and who took me to the New York Democratic Party Gala the night Bill Clinton was first elected; I let down a close friend who was devastated after a breakup by neglecting him because I was so overwhelmed with the pace and possibility of the City that was around me; I forged a bond of friendship that remains the strongest in my life, nearly three decades later. In New York, I grew up.

There’s another 33 1/3 book I’m currently reading that’s all about New York. This one centers on Some Girls, by The Rolling Stones, and it argues that this album conveys the essence of the City at that time, 1977/78, a precise place also convincingly portrayed in Spike Lee’s Summer of Sam and in several books I’ve read about the “Bronx Zoo” Yankees World Champions of that era. I like this 33 1/3 much better; it’s excellent so far, and it promises to be a standout in this great series. But like me, like you, the Stones were merely adopted citizens of the City. I believe the City may live in Mick’s body or Keith’s body like it lives in mine, like it lives in yours, woven now into every synapse and corpuscle for the rest of our lives. But the Stones cannot bring our New York to me. When I close my eyes, no matter what’s in my nose or pressing on my skin or on the tip of my tongue, if Lou Reed’s music is playing then I am all the way back, all the way again in New York.