Do images store themselves up in your dreams, like they do in mine? Do you find yourself in sleep, time after time, searching, searching, stubborn but slipping, through similarly structured spaces suffused with recurring sounds and retiring shadows that seem so solid but that, in their uncanny persistence, in their manic insistence, must ironically be drawn only by the questing mind?

I think you might, SD. I think you might because you love genre films and genre actors and genre writers and genre directors. You socialize, time after time, by mediating your friends’ recall of famous but sometimes forgotten faces. You quiz us, and the archetypes we’ve etched into our history of cinematic engagement, even into our engagement of our own pasts and so probably our own futures, are drawn back into relief.

Different genres of cinema function differently, and so, dear readers who are not SD: While you can watch Westerns without worry even if you read a comprehensive plot summary in advance, what follows will ruin all the fresh beauty of the Horror works discussed herein. ***SPOILERS ABOUND!!!***

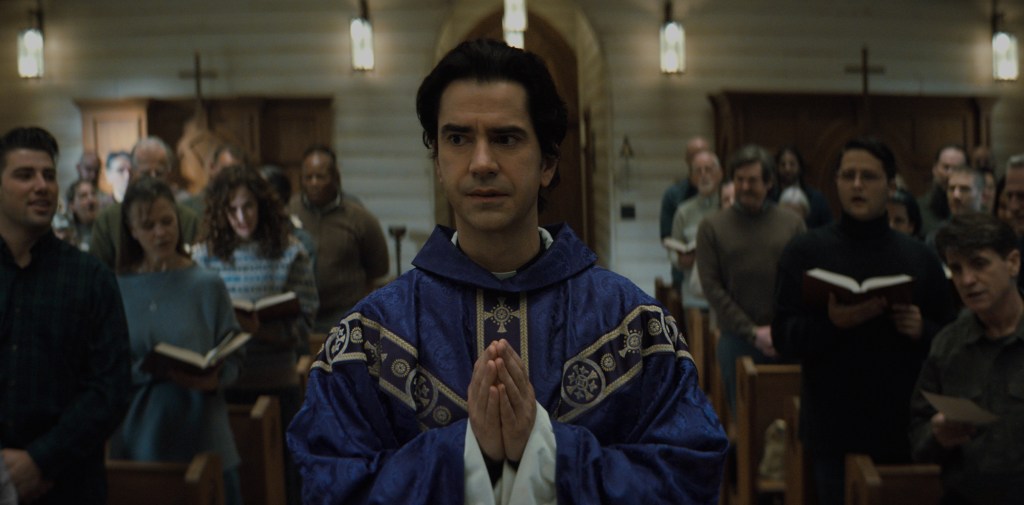

Archetypes breathe through genre pictures, and genre pictures breathe through archetypes. I think you feel this, too, because it’s not just past for you but a living reality that you shared several weeks ago when you reminded your friends, reminded me, that Midnight Mass is on. I needed the reminder in the midst of the incessant march of meaningless (for me) miniseries and limited series that literally stream (has there ever been a more fitting technological term coined?) around my every televisual movement in incomprehensible surges. Your post pointed to Midnight Mass as made by Mike Flanagan, and it held up the possibility that it would lead you next to The Haunting of Hill House and The Haunting of Bly Manor. And I was caught again, the images that have lasted in some cases three years for me—of the Bent–Necked Lady’s long fall along Nellie’s lifeline of nights of dread, of a sunny treehouse that is really a locked Red Room, of the Lady in the Lake looking with such love in so much aching vain for her little girl that the love becomes the deepest drowning pain—beckoning me. Midnight Mass? A must. Rewatches of both Hauntings? Oh yes. Explorations too–much–postponed of former Flanagan films? At last. Stirred, I set out to explore what called to me, what your post helped me redefine.

One thing I’ve found is that what’s lasted for me, those three images from the Haunting series that have endured—yes, of course it’s an obvious trope but this post is about genre cinema after all, the art of the obvious, the artful obvious, so yes, I’ll say it, they have haunted me, these three images—each of the three offers not a mystery but an unraveling of one. The Bent–Necked Lady and her archetype: ghosts embody intuition, a feeling forward, sometimes even a feeling for ourselves. The Red Room and its archetype: haunted places are holding traces of what else they might be for those who live inside them, Richard McGuire’s magnificent Here made mystery rather than history through horror cinema. The Lady in the Lake and her archetype: when we hurt too much, the pain spills over and stains the very land itself. My experience of the first two is merely penumbral; they have the right vibe for me, but they remain fictions I trust for their feeling. But the third; oh, my goodness, the third I know firsthand. Has your chance to live in Georgia yet drawn you to St. Augustine, a stone–structure–saddled tourist spot on the Atlantic Coast so chiseled by a legacy of violent racism that it used to proclaim itself the “first” American city? It probably still does. I went there at age twenty–two, a proud agnostic and rational skeptic (I probably still am), laughing out loud and in my head as we toured a fortress named Castillo de San Marcos and were told, as we roamed its massive mess hall, that in one corner of the vast room was a small door–shaped hole low in the great wall. This hole, we were assured, led into a dank space once used to torture captured people and now said to be among the most haunted places in the world. I must have audibly scoffed, snorted. What I know for certain I did was eagerly hustle over to join the little huddle of the unfettered and uncowed as we waited, one by one, to scamper inside on hands and knees (I doubt I could still fit in that access hole today). I couldn’t wait to be relaxed and jovial and to trivialize this snake–oil–gobbledygook about a haunted torture chamber. And today, more than twenty–eight years later, I am still waiting. Still waiting for the awful, awful feeling to leave me all the way, the feeling that drenched me with its putrescent agony in the scant several seconds I could stand to be inside there. I have no words adequate to describe how terrible it felt. Sure, science suggests that despite my hubris, I was conditioned psychologically to sense for suffering, to cling to the idea subconsciously that I professed to mock consciously, the notion that the pain of thousands of people had poisoned the place over hundreds of years. Maybe. But I’ll say confidently that the third archetype, the one invoked by the Lady in the Lake, the pain so deep it stains the very earth—I don’t feel it as mere fiction.

You know these three archetypes, I am confident, because they are powerfully rooted in horror cinema. What I have learned through reading Robin Wood, my very favorite author, and Jim Kitses, for a while Amy’s colleague at SFSU, is the generative aesthetic force of cinematic genre (no etymological divergence there despite disparate connotations, generative–genre). Wood happens to write about horror a little within his titanic oeuvre of film criticism, while Kitses happens to write almost always about westerns, but they both get it: They have taught me how cinematic artists grapple with tightly woven, inherited narrative structures and character types and visual palettes and through this grappling, through these constraints, innovate and energize. And your lovely posts honor this—not only by holding up exemplar after exemplar of a quality, yet humble, sometimes–in–the–shadows–of–history, film in genres like the romantic comedy, the screwball comedy, the film noir, the western, and the horror movie, but by inviting us to view again the images of actors who helped bring these films to life, actors who embodied the archetypes breathed into life by genre.

And my favorite facet of Hollywood films is the fusion of directorial vision and performative sparkle that, together, can over time when working collaboratively lend a genre depth and complexity and persnickety humanity and thereby give the lie to the sense that genre is mere formula and not constitutive of great art. Hitchcock and Kelly: Her vitality far too electric to be channeled merely into his misogynistic mazes. Boetticher and Scott: His athleticism and voice like burnished gold making liquid and lithe the stark dust of those craggy, claustrophobic visions of the frontier. And, I absolutely swear it, I stand by it, in a hundred years critics celebrating the auteur–star image axis in cinematic genre series will attend to Flanagan and Siegel: Her breathtaking (I’m not kidding, I feel her beauty in my lungs, every time I see her) marriage of stoic calm and searing desire the iconoclastic converse of the scream queens who for decades have lurched, within the very film itself usually, from befuddled ingenue to buffeted wreaker of vengeance, the events of the film making every decision for her. No one else decides anything for Ms. Siegel; you can see that clearly in every instant the camera finds her face, no matter how grave the horrors around her, no matter how haunted her past, no one else, least of all her own spouse Flanagan who writes her lines and wields that camera, and through their work together the genre is in this way marvelously inverted and reinvented.

When you wondered in your post about the relative strength of Bly Manor, with good reason, I recalled how the Lady in the Lake stays with me and thereby single-handedly makes this series stay with me. Why would the protagonist and co–writer of Hush, one with privileged access to the show creator’s ear, rate such mere supporting roles in Hill House and Bly Manor, I used to wonder? Yet like all good genre work, work in cinema that so often relies on a consistent ensemble of performers just as Flanagan indeed himself does, in these two series Ms. Siegel inhabits not necessarily the biggest role but always the right role: Theo is all stoic calm and searing desire, more than any other character on the Hill, and Viola is the living–and–unliving avatar of the stoic calm and searing desire that were necessary to turn the Manor into a burning hell of heavenly maternal love. In Midnight Mass, because the story demands it, she finally is this limited series’ star of stars. Just as we can imagine no one else inspiring the injury–yoked James Stewart to challenge himself to do better as well as Ms. Kelly does, just as we can imagine no one taller in the saddle nor possessing a more richly resonant voice of quiet authority than Mr. Scott offers, I cannot imagine how the boat scene in Midnight Mass in which Riley shocks us (sorry, I did not have it figured out until the moment itself, I love being a credulous viewer, the dropping of the second wedding band in The Sixth Sense remains the most shocking cinematic experience of my life and I am glad for it) by immolating himself would play for any other actor across the boat, any other actor I have seen, as well as it plays for the witness through whose eyes we watch it, the loyal and iron–willed friend Ms. Siegel patiently hearing along with us this bizarre tale of vampiric sanctification and awakening suddenly into a fury of rage and pain and grief and sorrow, her wracking sobs and echoing wails still leaving no doubt that she is the right warrior for Riley to have trusted with surviving him. No one else. Ahhh, Ms. Siegel (swoon). Like you, SD, and like Riley, and like anyone with any sense at all, I am in love with her. And with Ms. Kelly. And with Mr. Scott. This is something great genre cinema can stir in us.

As for The Sixth Sense and its trick, played on us in a manner that utterly depends on our willing participation in the Hollywood star system, the impossibility of Bruce Willis being dead ten minutes into a major release in which he’s first–billed, this trick still works when nuanced well. Midnight Mass starts with Riley, so we feel it as his story (at least in large part) even as a broadening ensemble of characters populated by the familiar Flanagan troupe burgeons over time. When he meets the angel at the close of “Lamentations,” the midpoint of the series arc, we are shocked at his early death and set up for the yet more cinematically luscious shock on the boat that closes “Gospels” an episode later. This director wrestles with the genre angel that was Hitchcock’s familiar but that Shyamalan, sadly, no longer will confront: the knowledge that horror films, that thrilling cinematic shocks of awareness, take root in us not through the sinewy twist of a cleverly held–back surprise but through the much firmer, more rigid vein of carefully cultivated belief.

As for Flanagan’s work with actors, I adore another one–off star in his oeuvre, quite differently than in the swooning sense but again with great admiration for both performer and director. Jacob Tremblay, star of Before I Wake, is the optimal Flanagan child actor because his “dark” side is grounded in the layered textures of the character’s own fears rather than in the creepy, unfocused, and unmotivated stares so common among children in horror cinema, while Tremblay’s “light” side, the dark/light juxtaposition in the child performer central to Before I Wake as it is in all films about scary kids, features his genuine sweetness rather than the bland saccharine style we typically see. The solid script helps this, to be sure, but the director/actor team is essential to its cinematic realization. As a side note, I adore young Tremblay more broadly; Room required him to hold his own in scenes with the marvelous (tee hee) Ms. Larson, and he handled the task, while I suspect I might like the astonishing Good Boys, at last a shock–through–childish–outrageous–antics comedy that instead of humiliating its characters actually loves them with all its heart, better than its creators themselves, in no small part because young Tremblay lends it his superb combination of angst and charm. But he’s no lesser a talent in the humble horror of Before I Wake, and Flanagan’s work helps us to recognize his thespian gifts. This, too, is something great genre cinema can stir in us.

Stirring suggests slow movement that in its whirling vortex disrupts the linear vector of time, and stirring is assuredly apposite when writing on Flanagan’s cinema. In his art, we return and return and return, spinning through his yarns. In his art, we are always partners in the taking up of rituals that hold fast against decay, against forgetting. We mourn spouse after spouse and child after child who have been lost from our lives too soon. We create routines to keep our awareness keen amid loss of hearing or sight. We look repeatedly into mirrors in order to complicate our limiting, time–and–space–bound insights. We cycle through rehab programs. We try and try again to make ourselves safe in the yawning expanse of home places by living in buildings deep in the woods or on vast estates with acres of property or on islands with thin traces of access and egress. We take mass. We bury cats and dogs and people. We are always, in this cinema, performing rituals. Well, the characters perform them, but of course this is the supreme secret of cinema: When the characters perform them, we do, too. The camera draws us into the rite, and especially when the rite is repeated again and again onscreen, establishing a rhythm as precise as the beats of a cut, we are within the ritual community. One way to see this is in the often more expansive cinematography of genre films: Even the most Academy–lauded fare is rife with two–shots and over–the–shoulder shots, hour after hour of chamber plays put on the big screen, but in the western the land is alive as a constituent force in the frame, and in the horror film we always, always, always know that something might be behind us or might be reflected in that window or might be haunting us through the limits of the camera itself. In genre cinema, we are making things happen, slowly, inexorably, by lending our belief to animate the monstrous creation stitched together with our willing participation. And in genre pictures above all, the ritual is where we’re at: the trench coat collar is always turned up against the urban rain in Los Angeles (what?? How the hell old is film noir?), the whip–witted lovers always have a near miss at domestic bliss, the hero always has to win a gunfight in a frontier town, and the blithely ignorant cop always misunderstands the true urgency of the evil curse in the town. We agree to be put through our paces, even when we hope that they will lead us someplace as surprising as where Flanagan takes us. We enact the rituals. In genre pictures, we make belief.

And I think that’s how he gets us, you and I, SD; that’s how Flanagan gets us and holds us. He knows that in horror, we make belief. His films are strong, but the limited series format is stronger for his art because we stir more slowly and so rise to more widely spanning perils of perspective. Characters grow and develop, and what haunts them telescopes through time and becomes much scarier than in the hundred–minute stand-alone slice. The rituals can be played out more patiently in the limited series. The jump scares and the viscerally lurid imaginings of creatures great and terrible, of ghosts pale and glowing, they are so much richer than what we’re typically made to watch in most horror cinema because every time, every single time, they are not our horrors, given to us presentationally, but the characters’ horrors, represented for us as we witness their confused striving for better understanding amid their chaos, as we willingly collaborate in their rituals of forestalling forgetting. We, like them, long to remember what we’ve repressed. How do we seek to repress? One way, I think, is through archetypes, through forming what’s too frightfully sublime to inhale into culturally resonant crystals that we can exhale one to another in the rituals of genre. Another way we repress, maybe, is through dreams. Doomed young Nellie hears early in her time at Hill House that dreams “spill over,” and in that same series her mother confuses the dream state and death itself with waking up. But is this confusion, or might she offer us insight? Do you, when you first wake, feel like I do that in that last dream, you could just about finally understand it all, you could just about grasp what you need so very urgently to know? If only you could remember. But if you’re like me, you can never quite remember what you think you might know. And so you sleep again, and you dream again, and the ritual begins again.

This, then, is why I think Midnight Mass, despite it lacking the literary wellspring of Jackson or James, despite its ending letting us down a bit like endings nearly always do, might be Flanagan’s masterpiece. I think it might because here in this series is the most careful and direct meditation on the germinal obsession of his art: The nature of belief, made collaboratively through ritual. And wow, did he choose the right medium for that obsession, or wow, did this medium choose the right artist. For in horror cinema, in nearly all horror cinema, the text is the uncanny, the ghostly, the monstrous, while the subtext is belief—the characters’ belief in legends, in what’s befallen them, in their own resourcefulness as they strive to survive. But in Flanagan’s horror cinema, the uncanny, the ghostly, the monstrous, these traces of what we earnestly recreate in our vain, ritualistic efforts to remember together what we have forgotten, all the established elements of the horror film genre itself, these are subtext; and the text, the text that glows with this inversion of the genre, that sometimes glows with the face of Ms. Siegel as she too inverts her own generic iconography, the text is how, together, we make belief.