I hear the clarion call and am pulled in with the tide of sound. You took up that call much earlier in life than I did, anchoring the horn to your own lips and hands while I let these sounds drift narrowly, only into the wells of my ears.

You weren’t charmed quite like Lee, though. He was so charmed as to take lessons with Brownie while still a teen. He rose, so young, to tower over the trumpets at his feet, to help even Dizzy’s mighty big band search for new bebop land, then to carry Art’s jazz message across the seas to Europe and Asia, then to slither to the top of the pops with boogaloo bite.

You and I know that they intertwine like that, like a fugue, Lee’s artistic development and the history of bop artists as jazz’s fleet vanguard. Their arcs encircle one another: From bebop, prodigious with promise for endless propagations of fresh music, to hard bop, smoothing out the edgy carping of birdlike complexities and sharpening the rhythmic pulse, to avant bop, dousing Rudy VG’s parents’ house in notes blue and new. Their darkest depths were likewise in the parallel motion of the most challenging charts, Lee’s heroin addiction a metonym for what felled so many of those with whom he shared a platform; luckier than some, Lee weathered that storm and kept his head. Kept moving forward. Kept growing. And then, so much more suddenly than they swelled, Lee and bop both crashed on the rocks.

You and I listen performatively and share our experiences with one another. We immerse ourselves in decades of sound. And if you hear what I hear, you hear strongly directed movement into new channels as the 60s turned into the 70s. Miles and each brilliant star in his mid–60s quintet went this way, the way of electrically amplified fusion with rock and r &b, and so did Freddie, and some of it was gripping but some of it was slipping, and these were the captains of jazz; this same movement led most lesser lights into much muckier musical places in which they seemed to stay too long, stranded. Whence the promise of bebop? Was the lithe, longitudinal insight of the acoustic combo lost, never again to be found?

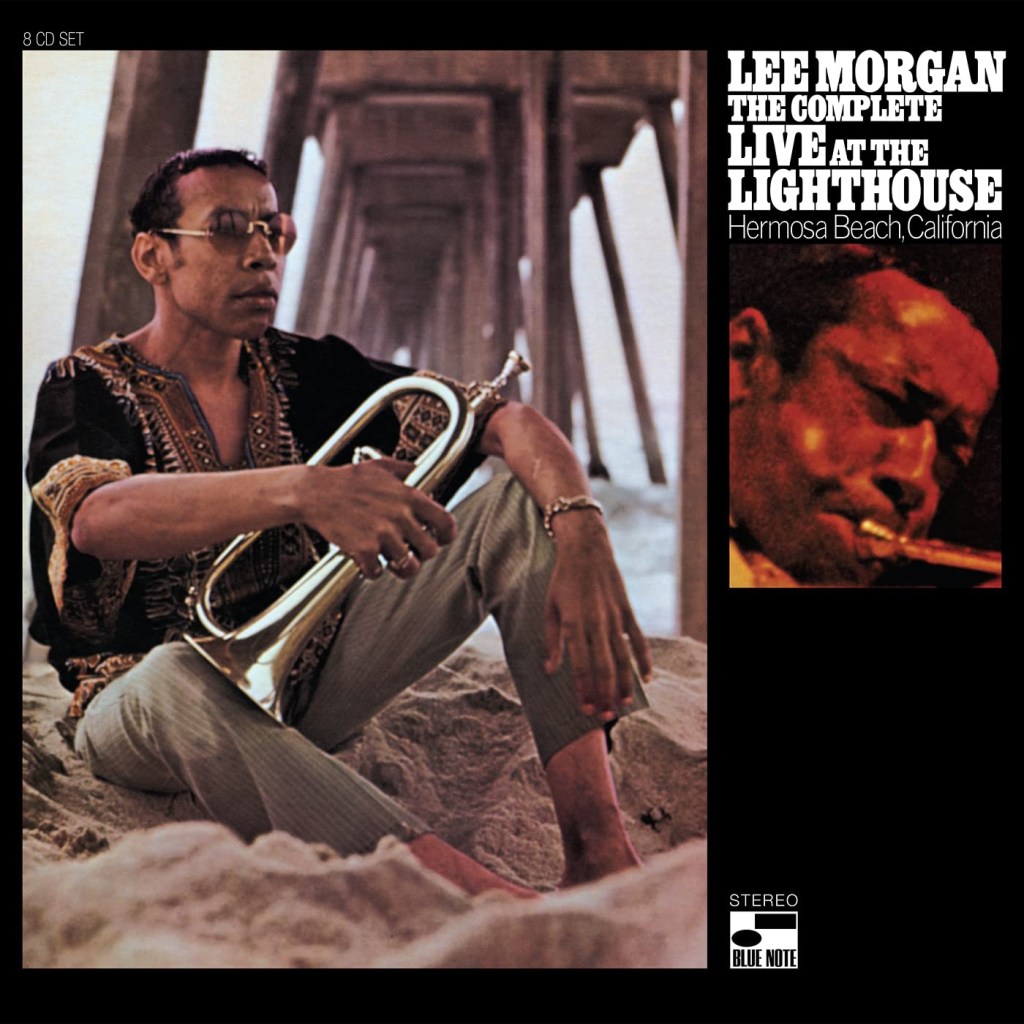

And Lee stood alone, quiet (Lee??? I lie) in comparison to his former stature, the desperate creatures craving popular praise swirling around him, and shone—I swear—like a bright and burning ray in bebop’s dying days. For a long while, I have read that Lee Live at the Lighthouse demonstrated that he showed that bebop was still vital, still fresh music. You know that I loved listening to the tattered three–disc set I’d felt fortunate to find used years ago, but—surely this is too pat, too cute, this claim that the set can show where Lee might have taken us next, if only he hadn’t been taken from us. Surely they exaggerate. Surely a collector who tries to attend to economic responsibility, even one as hungry as me, can’t suggest that I should spend EIGHTY DOLLARS on the new lavish box that features almost 40% of music I already own?

Worth every penny, my friend, all eight thousand pennies, every single one. I am astonished by this sublime listening experience. The acoustic bop combo, full of questing for the horizon, burns like fire on these three summer nights in Hermosa Beach. I do not have words enough to enmesh my feelings for these sounds. As someone stained by the guilt of my treatment of jazz like a museum subject through my greedy accumulation of objects, through my obsessive–compulsive organizing of my shelves, through my having never engaged a horn with practice and purpose, I can at least say this: From this extraordinary art form too soon dimmed, from this extraordinary life too soon dimmed, what light survives will, I hope, spark new fires and not just be trapped in the prism of curation.