Recently, I drew a card in a personal-reflection game created by Esther Perel. The card read: “The kindest thing someone has done for me is _________.” I responded by telling the story of you driving quite a large number of hours, alone, in the dark of the evening, to pick me up from the airport on a flight I’d hurriedly booked that same late afternoon; you dropped me at my mother’s house to share an all-too-brief yet miraculous and life-altering interval with her as she lay dying, while you returned to your place, hundreds of miles through the deepest hours of the night, kept company by the stars so omnipresent in the light-spare Florida sky, yet again in the car alone.

More than a quarter century later, I still sometimes count on you to lead me forward through the unknown. And you still respond with grace, patiently practicing your pedagogy as you support my hunger to grasp accretion discs and to grok stellar life cycles. Unknown to me, no mystery to you…but among the innumerable hands of Oklahoma and the groaning through puns and the joy of being with your great kid, I feel your driving me through the needle-carpeted palmetto brush of astrophysical wonders as a force that keeps me bonded with you.

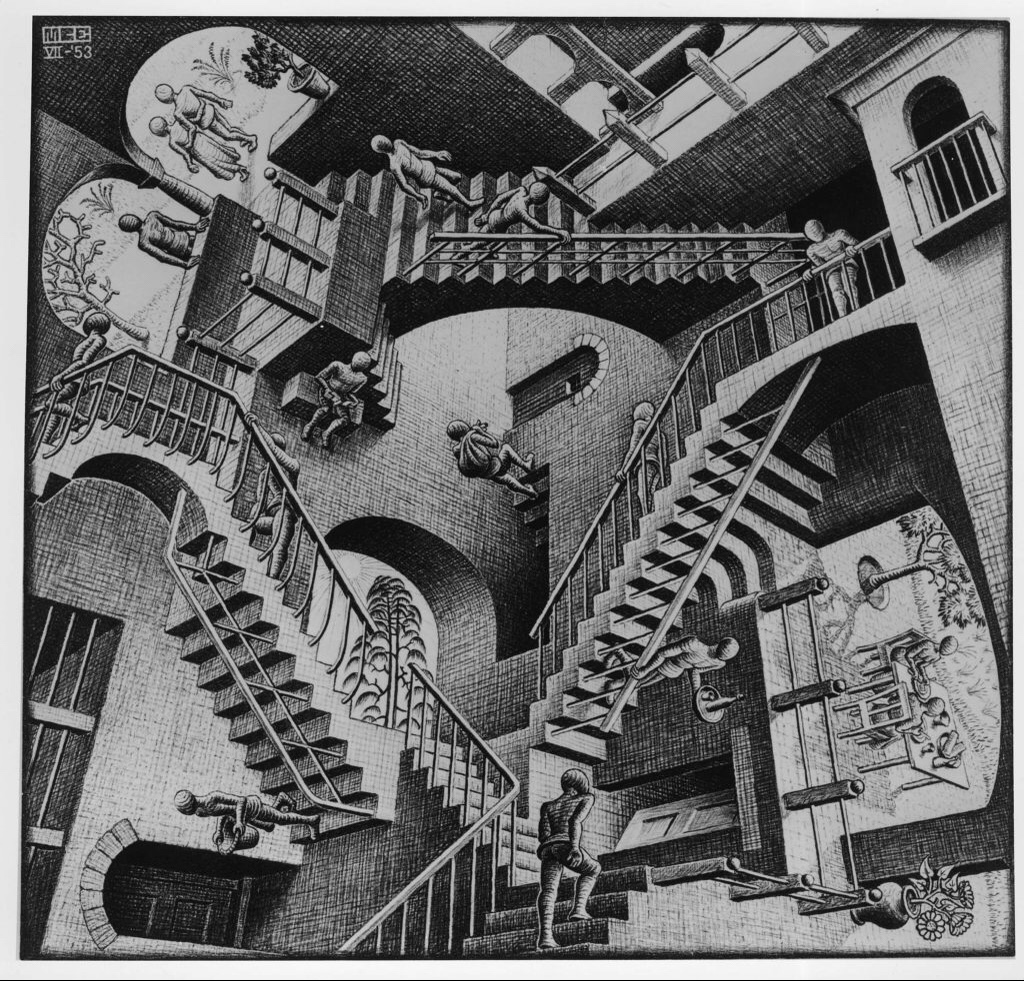

This is the vibe in my house as I see books that span similar scientific scope, books by Brian Greene and Randall Munroe and Richard Feynman with lines etched thickly in your direction. They rest, only sometimes read and then some only partially so, astride books by Stephen Jay Gould and Douglas Hofstadter. If only shelves could somehow structure themselves at the human scale with the dynamic architecture of quantum-level quickening, Gödel Escher Bach would bridge across the dining room to J.S. himself, and to the musical continuity measured by Beethoven and Brahms and then around the corner to the Beatles…and on and on…

Where you’ll find discontinuities: What proportions I’ve read, but also what proportions I profess to understand. I’ve confessed to you how my minimal math makes a morass of much of The Feynman Lectures, though I remain magnetized by his voice. Berliner’s Thinking In Jazz waits for me in another room, weighty not just in size but in musical examples decades ahead of my reading or hearing skills. So many of these books seem so separated from who I am now—beckoning me into a heady future that I yearn for but that for now is as hard to see as palm fronds in the humid Florida highway dark.

Tsundoku is the Japanese term for this, for filling one’s physical space with reading yet undone like an expressionistic sculpture of psychically longed-for learning. Taleb calls this accumulation the Antilibrary—linking the idea to Eco’s preference for personal library as fertile wellspring to both inspire and support more research and reference, rather than as moribund archive of already digested material. Like Hornby’s reveling in the unread as identity construction, Taleb’s Antilibrary is impelled to grow by revealing over time how much we don’t yet know, and his Antilibrary celebrates our impulse to cloak ourselves in what we still seek to know. The larger the Antilibrary, the more our multiplicatively indeterminate, yet powerfully directed, vectors amass our future readerly bodies.

In my cloak, I feel the interval between what I’ve read and what I will read not only as physical or psychological, but as relational. What I still seek to know matters most in my life because I have the chance to know more fully with and through others. A new friend in San Luis Obispo initially inspired this post through sharing with me an article about Taleb and Eco and the Antilibrary, but even more strongly through having shelves that honored Hornby and Feynman and Gould (here’s someone I can know, I thought). You, however, are the apt addressee because you teach me so much about what I still don’t know. And you are the apt addressee because you both figuratively and literally draw me closer, and drew me closer, to the mother who made me relational to my core.